The Wrong Firms Are Winning: China's Automotive Industrial Policy

Picking Winners is Hard for the Stock Market, and its Hard for Governments

Introduction

My claim below is that China’s policy towards the auto industry targeted losers, not winners. On that basis it is a failure. But first digressions background.

Chinese industrial policy is wide and varied. Furthermore, the current Made in China 2025 framework is a laundry list of industries, all with advocates within one or another ministry. As a professor I would tell students that if a boss tells you "here are your top 10 job priorities" they are either setting you up for failure or really don't know what you should be doing. For industrial policy, you can't promote everything, or you end up promoting nothing - everyone gets benefits, so no one stands as unusually favored. In the end, every part of the bureaucracy gets candy they can distribute. Plus make the list long enough, and one or two of the bullet-pointed entries will inevitably look good with hindsight. The leadership will be able to trot out "winners" that they "successfully promoted." Bollocks.1

OK, so how about for autos?

Regulations gone awry: US examples of unintentional industrial policy

First, as in all major markets, in China the auto industry is highly regulated from the perspective of safety, registration (to guarantee taxes and fees are duly paid) and fuel efficiency–cum–emissions. By and large, Chinese policy in these areas tracks that of the European Union, which in turn is quite similar to that of the US, Japan and Korea. In general, the industry is OK with such regulation as long as everyone is treated equally, even while the details may have significant impact.

Indirectly, and sometimes unintentionally, such regulation shades into “industrial policy” as the term is used by politicians and policy wonks. An example are the policies that turned the US market into one of SUVs and trucks rather than cars.

Start with the CAFE (corporate average fuel economy) standards in the US, which date back to 1975. By aiming for "neutrality” across vehicle sizes, they enabled the shift to large, gas-guzzling SUVs and not lower petroleum imports. (Europe is similar, except the beneficiaries have been large, gas-guzzling luxury sedans. Unlike CAFE, that effect was intentional.)

Then add the “Chicken War” of 1963, when a spat over frozen chicken exports to Europe that led the US to impose a set of “temporary” retaliatory tariffs. The list was carefully selected to affect only the US imports of one or two politically salient products per country, which furthermore in the aggregate matched the value of exports Europe was blocking. In the case of Germany, only one product was targeted, the VW “hippy” van that was exported to the US in small numbers. In accord with trade law, tariffs couldn’t target an individual country, so it had be a change of the tariff on an entire product classification. That meant an across-the-board 25% tariff on “light trucks.” But in 1963 only one light truck was imported from anywhere, so the resulting 25% import duty on all light trucks in fact only affected the VW minibus. Mission accomplished. However, temporary tariffs have a habit of remaining in place, and without competition, over time the Detroit Three2 made more and more vans and SUVs that for trade purposes were (and still are) classed as light trucks. Between the Chicken War tariff and CAFE, light trucks in the US rose from 30% of the market to over 70%. That segment is still dominated by Ford, GM and Chrysler, and are profitable to the point that the “Big Three” no longer make cars for the domestic market.3

The takeaway I emphasize below is that policy often has unintended consequences.

Intentional Policies in China

Electrification Policies

In the Chinese context, two sets of policies stand out. One is the promotion of electrified vehicles, which includes plug-in hybrids that can manage a minimum of 100 kilometers in pure electric mode.4 It only started in 2015, but until 2021 sales remained very low, so it wasn’t very costly. However, the per-unit subsidies were large enough to encourage the creation of paper entities that collected millions of dollars without ever producing anything, and it took a couple years for the government to put a stop to that.

As sales increased those national-level subsidies were reduced and then went to zero on January 1, 2023. As one would expect, there was a surge of EV sales in November and December 2022, in anticipation of subsidies being removed, and indeed EV sales plummeted 50% in January 2023. What was not expected was that by June 2023 EV sales surpassed their December 2022 peak, and the share of New Energy Vehicles (EVs plus PHEVs) rose thereafter from what proved to be a temporary trough to comprise over 50% of the market since July 2024. I strongly suspect policymakers did not expect that, but what career-conscious official would admit to that?

[Note that from June 1, 2024 there are again national-level sales incentives. The new “cash for clunker” subsidies are a response to slow economic growth and include gasoline-powered ones. Subsequently 20+ cities and provinces added local subsidies, with varying amounts and requirements. The initial plan was for the national incentives to expire Dec 31, 2024.]

Electrification is a side story, to which I return in a bit.

Joint venture policies

The other, longer-lasting policy was to force the global OEMs to enter the market via 50:50 joint ventures with Chinese state-owned car firms.5 In return, local partners faced a mandate to learn from their foreign partners, who were encouraged to teach production know-how and set up local engineering centers. The goal was to strengthen a set of car firms located in big cities that were not only local employers but were owned by one or another governmental entity, overseen in places such as Shanghai by the politically ambitious. These were first and foremost the First Auto Works (FAW) and the Second Auto Works (renamed Dongfeng) owned by the central government, whose names indicate their historic importance. In addition, there were 4 additional producers controlled by provinces or large cities: Shanghai Auto Industry Co. (SAIC), Beijing Auto Industry Co. (BAIC), Guangzhou Auto Co. (GAC, in Guangdong), and Changan Auto Co. (in Chongqing). Hence we had Beijing Jeep, Changan Ford and Shanghai GM. Honda set up JVs with Dongfeng and GAC, Toyota with FAW and GAC, and on and on.6

These government-owned firms were thus targeted to lead the auto industry as domestic firms gained experience and took share from the foreign-based leaders of the global auto industry.

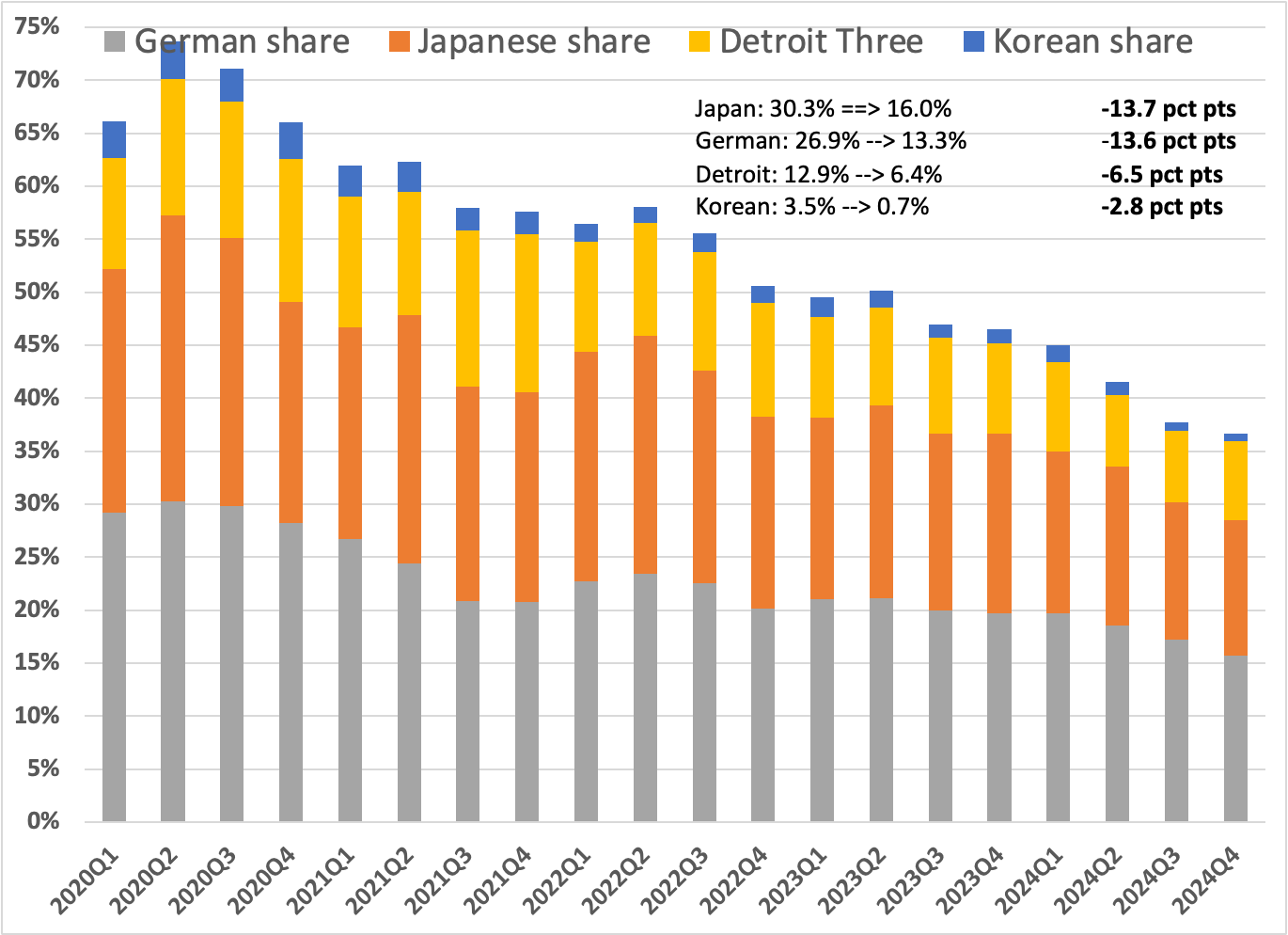

Now domestic Chinese producers have indeed displaced the global OEMs, whose share fell precipitously over the past 4 years, as per the following chart:

However, it was not the putative domestic champions who ate the lunch of the global car companies. It was private firms who lacked the cushion of profits from a joint venture, above all BYD, but also Li, Chery, Geely and Tesla.7 Collectively these 4 firms went from 10.8% of the market in 2020Q1 to 36% in Oct-Nov 2024, while the joint ventures went from a peak of 74.4% in 2020Q2 to 37.0% the past 2 months.

Meanwhile the national champions went from 16.2% in 2020Q1 to 14.9% the past 2 months.8 If we add in the collapse in sales of VW, GM and their other joint venture partners, the overall SOE drop is catastrophic.

Winners, but the Wrong Ones

As I view it, Chinese automotive policy has not been successful. Yes, the purely domestic end of the industry is doing well. That result, however, is dominated by Geely (which started as a major player and continued to pick up market share) and above all by BYD, which went from an insignificant 1.0% share in 2020Q1 to displace VW to become the largest player in the domestic market. However, the government poured resources into their national champions, by allowing them to pocket half the profits of their joint venture partners. Until recently the joint ventures of VW, Toyota, and Honda were very profitable. No longer. Several have been shuttered (Suzuki, Mitsubishi Motors, Jeep) or are unimportant (Ford, Stellantis and Renault). VW is closing plants. Looking only at their own sales understates the magnitude of the collapse of China's national champions.

China is not unique in this. Japanese nationalism led to the shuttering of Ford's operations there in 1936, just as construction began on a huge plant in Yokohama that was intended to serve as their export base to the rest of Asia. It took another 40-odd years for Japanese car companies to achieve success in international markets. Furthermore, the initial national champions were Isuzu and then Nissan. Isuzu exited the passenger car market over 25 years ago, and Nissan now faces a forced merger with Honda after a government-supported coup against Renault that led to chaos in Nissan’s operations both in Japan and overseas.

So don't accept claims of the power of industrial policy at face value.

Afterwords: Picking Losers

All the above in fact paints too rosy a picture, because a variety of local and provincial government entities also play investment banker to private startups. A long Yicai article compiled data on investments in 23 different such automotive ventures across 13 provinces, to the tune of over US$90 billion in investments. Of these 23 firms, only 8 are still in existence, and of those 8, two have minimal sales. In the aggregate the plants of these 23 firms were expected to add 13.6 million units of new assembly capacity, but 10.3 million units of that intended capacity have been shuttered, with most of the plants never building a single vehicle. So we have Tianjin and Guangzhou putting a combined 元130 billion (US$1.8 billion at 元7 per US$) into Handa. They picked a loser, not a winner, and that money is gone. There is only one success story, small investments by Beijing and Changzhou in Li, which is not only producing vehicles but is making a profit. With a 1 in 23 track record, trying to pick winners is clearly a very bad idea.

For careful explication of this logic, see Ryutaro Komiya, Masahiro Okuno, and Kotaro Suzumura, editors, Industrial Policy of Japan. Academic Press, 1988. Original: 『日本の産業政策』 小宮隆太郎・奥野正寬・ 鈴村興太郎編。東京大学出版会、1984. Mea culpa: I was the co-translator with Anil Khosla, an academic based in the Netherlands.

Actually the Big 3½, since this was before Chrysler acquired American Motors.

OK, there are exceptions such as the Ford Mach-E and the GM Corvette.

Note these policies encouraged de novo entry, with Nissan setting up its Smyrna TN plant in 1983 specifically to build the Nissan Pickup, later renamed the “Frontier.” Nissan was followed by Toyota, which builds the Tundra in Texas. Meanwhile, the 1966 Auto Pact and later (in succession) the US-Canada Free Trade Agreement, then NAFTA and currently the USMCA, allow tariff-free trade within North America. The Chrysler minivan, a light truck, was (and still is) assembled in Windsor, Ontario but under the FTA was not subject to the 25% Chicken War tariff. Mexico now also builds light trucks.

Those policies include the lithium battery supply chain and charging infrastructure. I do not know enough about the firms involved to know whether they fit the who-didn't-win pattern I trace in the core of this article.

Despite tariffs, imports remained high, at 1.1 million vehicles in 2019, in what was an overall smaller market. They are on track to be a bit over 600,000 in 2024, in a larger overall market.

Note that late Premier Zhang Zemin was an electrical engineer whose first job was in the auto industry. From 1985-1989 he was the mayor of Shanghai, where not by chance the joint ventures of VW and GM were located, as well as many of their European and American-based suppliers.

Not all private firms grew over the past few years. Great Wall had 3.2% of the market in 2020Q1, but peaked at 5.7% in 2021Q1 and only had 2.5% in 2024Q2. Its strongest products are SUVs, which unlike the US do not dominate the market in China.

The large number of (to date) highly unprofitable new entrants that focus on EVs went from 0.2% to 6.1%, while Tesla went from 0.5% in 2020Q1 to 2.4% in October-November 2024. These include one-time stock market darlings NIO and Xpeng.