Obviously I’ve fallen behind on my target posting rate. Given today’s headlines, here’s a simple analysis that I presented to Econ 101 students decades back. For addictive substances, supply-side policies don’t do much. To be effective, any policy has to focus on the demand side. Read on to understand why.

Basically, if you raise the price you get a large increase in supply. So it doesn’t take a huge increase in price to get you back to the starting point. Especially if demand doesn’t change much with price.

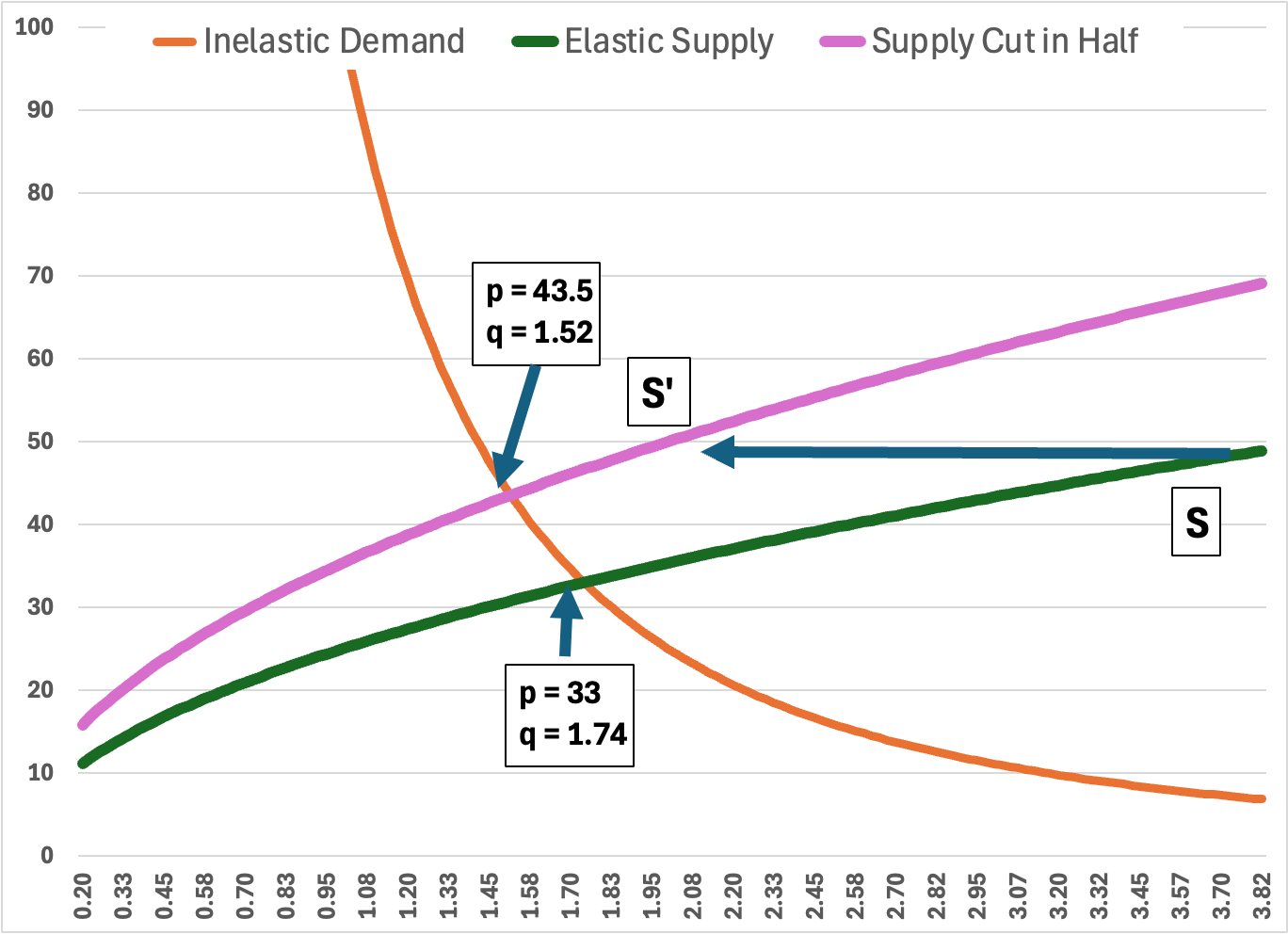

Now I did this initially for cocaine, and could use the fact that most agricultural commodities are quite elastic in supply, if you see an increase in your “farmgate” price you can cut back on another crop to increase output of coca leaves. Fentanyl has multiple routes to synthesis, and there are several similar synthetic opioids. My hunch is that if you doubled the price out the door of illegal labs (or legit labs in China that don’t face export controls), in a short time you would see output more than double. For the graph below, I assumed that if prices increase 10%, output increases 20% (an elasticity of +2, in line with the empirical literature for cultivated crops).1

Now to demand. Fentanyl and other opioids are highly addictive, or we wouldn’t have much of a problem. Addiction means, however, that if you raise the price by 10%, output doesn’t fall much, say 5%.2 Translate that into economic jargon, and demand is quite inelastic. (For those remember Econ 101, I use an elasticity of -0.5.)

So let’s use these elasticities to generate an appropriately shaped demand curve, an appropriately shaped supply curve, and a post-border-crackdown with the supply curve shifted left by half – that is, at any given price, we stop half of what smugglers attempt to bring into the US.

So what happens? Price goes up by 32%, and quantity falls by 13%. Would that change be visible in hospital emergency wards? On any given day at your local hospital, no, it would take months to be sure it wasn’t just a spate of short-term luck. The US death toll from drugs would remain tragically high.3

Now over time the higher price might in principle keep a few people from becoming addicted, but people probably have enough cash before they’re hooked that $40 on the street for a “legit” multi-day patch is affordable. Pills of unknown origin and strength can be had for a dollar.4 So a higher price is not much of a barrier. The real cost isn’t financing fentanyl purchases, it’s the impact on health and the ability to hold a job. And the money wasted on the futile attempt to police of our borders, and policing the police to limit corruption, for something that’s small and easy to smuggle.

It’s easy to afford to get addicted, and easy to afford a fatal overdose. Draconian border controls won’t change that.

I do not know what the DEA would consider “success” in interdicting illegal drug imports. I suspect that stopping 50% of the quantity hitting our borders from getting across is very, very challenging, even with Mexico and Canada helping – a fairly small package of pure fentanyl can fill many thousands of pills. Remember the supply elasticity logic: a higher price means more drugs reaching to border, and so at the end of the day the net change in quantity is less than 50%, or whatever the target is.

Of course, we haven’t been able to stamp out meth labs in the US (or where I live in Virginia, moonshine). Why would illegal fentanyl labs be any different? Stopping half of all smuggling raises prices by no more than the 25% tariffs now being placed on legal imports!!

See this article on the low prices in San Francisco, and interviews with users suggestive that higher prices won’t change demand by much: https://sfstandard.com/2024/01/22/cheap-street-fentanyl-san-francisco/

The bottom line is robust qualitatively, but the numbers change with the starting points of the curves. Above I used the standard formula, which has positive demand even at an unrealistically high price ($100,000 a dose) while demand increases without limit as the price falls towards zero. Even if free, only so much fentanyl could be sold. Shifting the demand curve both left and down changes the numbers, but actual quantities still fall by less than half. For empirical work, economists don’t generally observe near-zero prices or prices so high that demand is minimal, so they don’t pay attention to whether the parameters that statistical programs spit out imply odd behavior outside the range of observed data.

See https://washingtonstatestandard.com/briefs/price-of-illicit-fentanyl-in-wa-drops-to-as-low-as-50-cents-a-pill/ and https://kstp.com/kstp-news/top-news/price-of-illicit-fentanyl-drops-to-dangerously-cheap-in-twin-cities-metro/. Street drugs one day may “cut” so that you need to take 2 to feel anything, while the next day they are higher quality and 2 is a fatal overdose.