China's Policy Context

Crisis Management not Fundamental Reform

Context

The Chinese government is fixated on growth, for good reason. The last major recession was in 1989, the year of the Tiananmen protests. The current leadership remembers that well – Xi Jinping was 36 at the time – and fear a repeat. Hence when the global financial crisis and subsequent Great Recession broke out in the US and Europe in 2008-2010, China pulled out all the stops. The subsequent construction spree created China's modern expressway, airport and high-speed rail networks. The bottom line: no recession, no domestic unrest.

In 1989, however, there were only 576,000 new college graduates. They were urban, interconnected (via on-campus networks and intercollegiate activities) and desperate for jobs. In 2023, there were 10,470,000 graduates, some 18 times more. They too are urban, networked, and desperate for jobs. The political saliency of youth remains, but now faces proactive repression. Creating sufficient jobs is, I judge, a vain hope.

Current Policies: Crisis Management

The government has few tools to generate growth. Modern infrastructure has been built out at both the national and local level, and the government is unwilling to engage in direct fiscal policy to add to it. Since China's 1994 tax reforms, local and provincial governments cannot impose additional local taxes, or divert national taxes to their own pockets. Their interim fix was to sell land, but the real estate crisis means that is no longer possible. Developers can't sell existing condominiums and office space, particularly the 200 or so lower-tier cities that only have populations of 1-3 million. That weighs on the financial system first and foremost, and secondarily on growth. Meanwhile, China’s senior leadership has emphatically reiterated that they won't directly subsidize consumption.

Their principal remaining tool is to push banks to lend more to large enterprises. Since many firms have excess capacity and growth is slow, slighly cheaper financing would not normally have much impact.1 However, the government directly controls large firms in many sectors, and has been increasing the power of Party Committees in private large firms. So lower rates will be accompanied by increased borrowing and related investment projects. Large firms, though, are capital-intensive, so such projects will generate few jobs.

The real impact of lower interest rates is to help banks roll over loans to distressed real estate developers, to stem additional collapses such as those of Evergrande and Country Gardens. Secondarily, banks can roll over their loans to distressed local governments, which without the revenue from real estate sales are finding it hard to pay salaries. Laying off teachers and hospital workers is not good for short-growth or the reputation of the leadership in Beijing.

Whatever the rhetoric, the focus of current policies is crisis management.

The Challenge: Getting Households to Consume, not Save2

The only part of the economy that might undergird growth is household consumption. The challenge is that households feel compelled to save, not consume. Why? – an aging population combined with rapid growth. A quarter century ago only 10% of the population was over age 65; in 2023, it’s 23% of the population. Unlike the US and Europe, and many economies in the rest of the world, China has no national pension system and very little public health provision.3 Furthermore, with the norm of one child since 1980, the extended family doesn’t extend very far. Parents can’t depend on children to support them in old age. They have to save. A lot.

The second problem is that 40 years ago, when those facing retirement in 2024 began earning income, China was still very poor. What workers saved when they were young doesn’t add up to much today, when the standard of living is much higher. Of course, much of the population – for example farmers, and the owners and workers in small restaurant and shops – keeps working after age 60. But they still save, because they know they can’t work indefinitely, but can expect to live into their 80s.4 However, with the end to pervasive hunger, a diet heavy in white rice means perhaps 1 in 5 older Chinese have diabetes, while 300 million cigarette smokers breathing urban smog means lung disease is epidemic. Chronic illness is already pervasive. People don’t die of good health.

Basic Data

How much savings is enough? A few graphs, reflecting simple spreadsheet calculations, show that even saving 30% of income doesn’t get you very far. First, in 1985 average disposable income was only 元479; by 2023, the level had risen to 元39,218 (at 元7/US$1 that’s $5,600 a year). The average, of course, is lowered by those too young and too old to work; actual wages are higher. Play around with a spreadsheet, though, and you’ll find it’s the overall trend that matters, and not the choice of income versus wages.

As a start, note the sheer growth of incomes, which lifted the overwhelming majority of the population out of poverty. As to the data, some of the growth reflects inflation, but that turns out not to matter when thinking about saving for retirement. Plus even with inflation, growth remained very high, as per the second chart.5

Savings Rates and Cumulative Savings

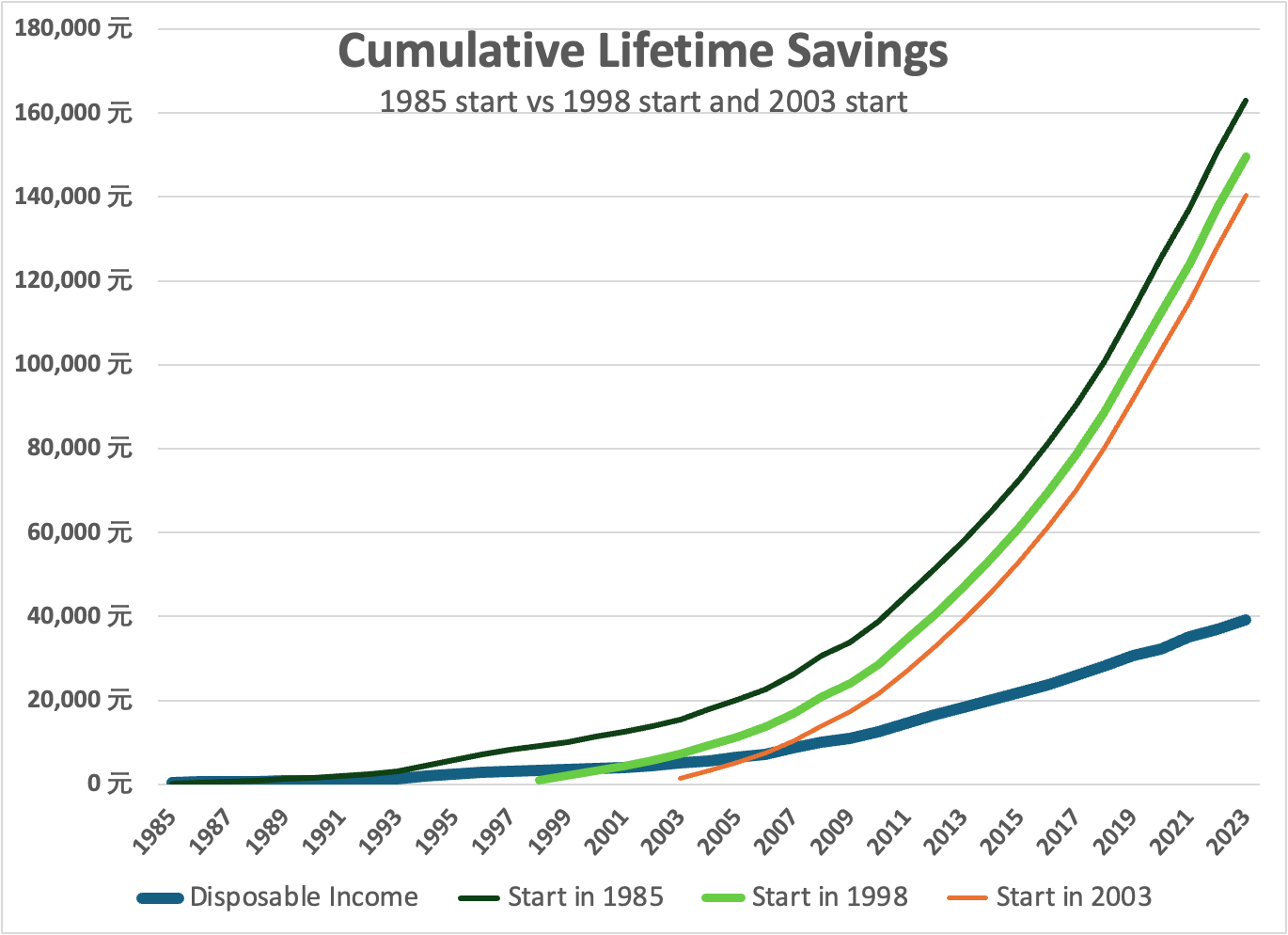

Let’s assume that households save a modest 30% of their income. (The 2023 US rate was 4.5%, so that would be a stupendous sacrifice from our societal perspective.) How fast does that 30% accumulate? The answer is: not fast enough. Because nominal and inflation-corrected incomes rose so rapidly, only savings over the past few years matter. In the base chart that follows, I assume that the income on savings is only enough to offset inflation. (I explore what happens if you could earn good investment returns later.)

Starting saving while young doesn’t make a large difference, Looking back, even diligent saving while poor puts paltry sums in the bank.

Savings still appear to cumulate to impressive amounts. Reality check: the higher amount, from those who started early, is only 4.2x current income. Since savers are living on 70% of their income, it actually covers 5.9 years at current consumption levels. For someone hitting age 60 this year (so born in 1963), that unfortunately doesn’t get them to age 70, much less cover their full 20 years of expected remaining life. If you want to cover 10 years, you have to save an unrealistic 50%. In reality, you can’t voluntarily retire, and must keep earning income as long as you can.

How much do things improve if you can earn a return above inflation. The answer: by quite a bit, especially as returns increase. (The legend is hard to read. The baseline is real income, the next is keeping up with inflation, the third is earning a return 5% above inflation, and the top red line is earning a return above inflation equal to the (real) growth rate.

If you can just offset inflation, with 30% savings you end up with enough to cover 6 years, as above. If you can get a 5% real return, that improves to 12 years. Not enough. But if you can earn a return that matches the growth rate of the economy, you have 19 years, enough for a frugal retirement. Earning a return equal to the economy’s overall growth might not seem an unrealistic. It is proving very hard in practice.

Implications: Scams and Speculative Investments

For Chinese households, this need to save, and then save some more, obviously puts a dent on one’s lifestyle. You needed to do much better than just putting money in the local postal savings bank. That’s because, to help fund industrialization, the government mandated that the interest paid on postal savings and bank deposits be kept low, in fact lower than inflation. You could never get ahead just by setting aside a portion of your pay in the bank.6

The problem is that everyone across China was facing the same challenge.

Investment trusts and real estate came to the rescue. Until of course they didn’t.

Flipping Condos: The Lucky Urban Elite

For urban residents who got ownership of their company apartment when many firms stopped providing such benefits in the mid-1990s, things may have worked out pretty well. That first condo freed up resources, and in addition workers at urban state-owned enterprises often started off with a good income. (Things didn’t work out so well for those down-sized.7) Flip a couple more times, reach a management position, and have a spouse with a good job and life could be quite comfortable.

The Stock Market

Stock markets are another alternative, but “hot” money seeking quick returns has made those in China extremely volatile. Look at the Shanghai Stock Exchange, China’s largest. Over the past 20 years, for example, there have been 10 years when the SSE Index declined, including 7 years with double-digit declines. In 2023 the market was lower than during the previous 10 years. If you timed things correctly, fine, but few who made a short-term profit could resist putting their money back in the market. It was not a good way to earn a steady return towards old age.

Investment Trusts

If you walked into your local bank, at least anywhere outside the handful of China’s largest cities, there would be a desk offering investment trusts. These would consist of a package … well, the actual investment details were often vague … of investments in and loans to local government projects in which the bank had a hand. The money typically flowed to Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs), which then relied on the local government to fund repayments, because many infrastructure projects generated no revenue. Others flowed to real estate developers. Now real estate developers are struggling to stay afloat, while local governments have seen their incomes plummet and can’t pay off their loans, either. If you read the fine print, the bank made it clear that they weren’t responsible, they were just renting a corner of their lobby. You can’t liquidate an investment trust, or at best can get out only a portion of your investment.

Direct Lending to Small Businesses

Finally, there were local brokers who solicited loans to local small businesses. These were totally unregulated, and some were from the start Ponzi schemes that deliberately defrauded investors. Even without malice aforethought, they were run by inexperienced managers with no capital reserves working with a limited number of clients. At best they were illiquid, and as an informal financial transaction the brokers would have little recourse if a borrower failed. Those placing their savings might know the local businesses and feel like they were helping their community, and initially returns were often quite good as new borrowers kept current on repayments. The reality was that small businesses failed with great regularity, so high returns didn’t last, and most savers lost some or all of their investments.

Summary

The reality was that despite astounding levels of economic growth, few savers earned high returns. Households continue to set aside 30% or more their income.

Had the Chinese government set up a national healthcare system and a basic pension system early on, households could instead focus on only saving enough to supplement their pension and the many indirect costs that accompany a major illness. While formally socialist, the Chinese Communist Party failed to practice what it preached.8

The institutions inherited from Mao did not help. Rural China was outside the national administrative system; communes were expected to be self-governing and float on their own bottom. Each commune was responsible for the feeding, housing, education, healthcare and old age care for its residents.9 The commune was expected to pay taxes in kind, be it grain or cotton, to support the cities that were the locus of industry and the rural elite. They got nothing in return, except the privilege to buy industrial goods at inflated prices, another form of taxation. When the communes were abolished, locally provided public services suffered, in part because the local government structure that took their place was starved for resources, while no longer being able to train and assign promising youth to jobs as local teachers or barefoot doctors. Urban residents lived in workplace collectives, where were likewise expected to house, feed and education members. They fared better, but only in relative terms; ditto the miliatry.10

Conclusion

It is too late now. Policy cannot rebalance demand away from the investment towards consumption.11 The government’s latest set of policies can and will stave off financial crisis. They will not fix the slowing economy.

While the government is paying more attention to the ills of the healthcare system, that system faces the legacy of decades of underinvestment. And where will the required doctors, nurses and technicians come from? – the working age population peaked in 2014. Meanwhile on the demand side, by the end of 2024 those of retirement age will be more numerous than children, while requiring far more health-related services.12 Under China’s effectively privatized healthcare system, investment in physical facilities lagged, pay was low and so was status. Medical doctors subsist on envelopes of cash from patients’ families to supplement their salaries, and are not part of China’s elite. So all too few of this year’s 10+ million college graduates are trained to fill those slots. The need for those envelopes of cash is one reason that families must save rather than consume.13

Notes and Asides

Until the 1990s, Chinese “banks” were extensions of the state, an adjunct to the central planning system, and not deposit-taking and lending institutions. As they developed into modern banks, they had limited institutional capacity, that is, no experienced loan officers. They thus focused, and continue to focus, on large loans to large borrowers. Small business lending and personal finance remain underdeveloped, and in any case small changes in loan rates don't get consumers and small businesses to borrow more; their behavior is dominated by changes in income and revenue.

In the US, interest rate policy works through changes in mortgage rates and car loans, as they feed directly into lower monthly payments. However, in China cash remains central for buying a new car, not bank loans. For real estate, "investing" in a condominium requires 30% of the purchase price up front. Units are typically sold before construction starts, and mortgages are of short duration. Monthly payments start immediately, that is, before construction. Cheaper mortgage rates won't do much to increase interest in purchasing assets that are falling sharply in value. However, it is important for the government to see that existing projects get completed, to preserve construction jobs, to keep banks solvent, and last (and least) to see that households eventually end up with a completed condo.

Remember (hey, I’m an economist!) that GDP = Y = C + I + G + Net X, that is, Consumption plus Invesment (in roads, buildings and factories, not financial “invesment”) plus Government Purchases plus Net Exports. The largest of these is Consumption, so “rebalancing” the economy away from a reliance on I and G to C potentially has the biggest impact on short-term growth.

Large metropolises such as Shanghai limit access to public healthcare to official residents, which excludes the migrants who comprise most of the population. However, decades of underinvestment in expanding the number of healthcare workers and facilities mean that even those with access generally face large out-of-pocket costs.

Life expectancy at birth is now age 78. For an extended non-technical discussion, see Wikipedia entries on Aging of China and Demographics of China. The WHO published detailed mortality data. If you want a technical discussion, then you likely have access to a university library and can readily locate articles in the relevant public health and demographics journals.

I calculated the geometric mean, the proper way to average growth rates, which was 9.8% over the 2 decades of1992-2012, and 8.6% over the last 3 decades of 1994-2023.

Such “financial repression” is not unique to China. Policy in the US likewise kept interest rates below inflation in the 1970s, and until the 1990s in Japan. When I got married, I was working kitty-corner from the New York Fed. My wife and I liquidated our savings accounts, the most munificent of which was paying 7%. I carried a frightening large wad cash to the Fed window and instead purchased a short-term Treasury paying 16%. It rolled over automatically and at peak paid over 20%. That same arbitrage led to the creation of Money Market Mutual Funds and the rapid ascent out of nowhere of Vanguard with its no-fee, low load model. Tens of billions flowed out of banks, forcing interest rate deregulation.

See the 2000 film Happy Times for a depiction of downsized workers in Dalian struggling to make do.

OK, in China orthodoxy means Mao over Marx, but those at the top know their Marx, even if college students aren’t schooled to read widely.

Local leadership was required to learn and adhere to the Party line, so for the first time in Chinese history the political system reached down to directly interact with peasants.

The military, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) also ran farms and factories. Even if they received support from the central government, they were responsible for the provision of housing, education, healthcare and so on for Army members and their families, outside the administrative system of local communes or cities.

Exports provide no help. They reflect a surplus of manufacturing capacity relative to the domestic market, whereas labor productivity continues to outpace the increase in demand. Manufacturing is thus employing fewer workers, not more. In the US, the share of people working in manufacturing has been shrinking for the past 75 years. Today healthcare employees a significantly more. The idea that we can bring jobs home is nice rhetoric, but defies the reality of the skillset and preferences of our workforce.

Most Chinese youth continue to high school; the statistical system continues to reflect an earlier age when work started with the end of middle school. Similarly, the 65+ age bracket does not reflect the reality that outside of workers at large firms, retirement for older workers is an aspiration, not a reality.

I chose not to approach this issue from the standpoint of intergenerational transfers (Ronald D. Lee and Andrew Mason) or generational accounting (Lawrence Kotlikoff, Allan Auerbach and others). In terms of my argument here, they would emphasize that you can’t save today to provide healthcare tomorrow, as personal services can’t be transferred across time. China is no longer poor, so most Chinese consumption consists of services and secondarily non-durable good. As a first approximation, then, all resources for tomorrow’s retirees have to come from the services provided by tomorrow’s workers. With a rapidly declining ratio of workers to retirees, well, it’s not a problem unique to China.

yes, but most of the written is similar for the US

among others (which probably seems most far reached, but it is not) is the fact that financial crisis every so often wipes out a lot of people.

not to speak about manny Wall street scummy products (which are usually technically legal) who do the same to number of people day by day.