China: A Price War? – maybe not!

Discounting is rampant, but in line with changes in supply and demand

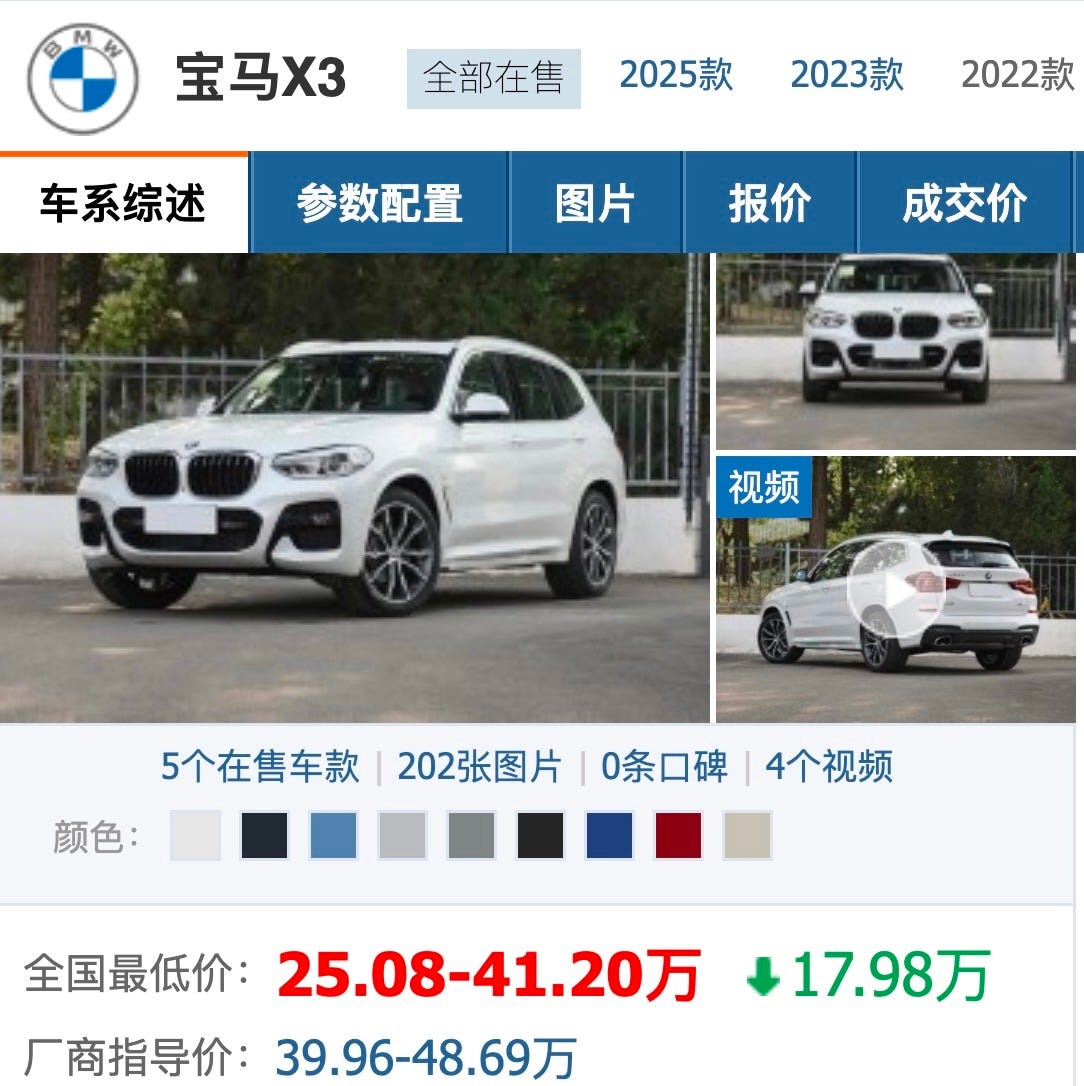

How about getting your new BMW X3 at US$24,800 off (元179,800)? That's the sort of pricing we see now in China.

Now that's just one brand, and an expensive ICE, so maybe not representative. So I cast the net wider, using data from February 14th for the 300 or so best-selling models. The average discount: 元42,600 or about US$5,900. It sure looks like a price war!

Price wars – like any sort of war – aren't a normal situation. However, to the delight of consumers, and the misfortune of producers, they do happen. Let's look at the analytics.

Introduction

Autos are highly differentiated, durable consumer goods the production of which incurs high fixed costs. Uh, OK, I will refrain from jargon.

Analytics: the consumer side

To start with, consumer tastes and use cases vary widely, and the Chinese industry has responded by offering a choice (in February 2025) of 257 models popular enough to sell 1,000 or more, and another 359 slower-selling models, or 616 in total. And that's not counting imports such as Lexuses, Porsches and Ferraris.

Now at any given time a few models will bomb, as what the boss thinks looks great fails to resonate with the public. The responsible firm will be forced to cut prices to move the metal. No price war there, just the idiosyncrasies of trying to predict consumer tastes. Now predicting the future is hard enough, but it's made harder because it takes 2 years (or more) to go from a stylists' sketches to building a car with new sheet metal. Furthermore, that's done with only a general idea of the new cars that competitors will be launching. Flops are inevitable – while on occasion a model only gains traction after a year or two, when it's "ahead of its time".

Cars also stay in production for several years, and over time prices will be cut as they lose their styling edge and as used vehicles become available and start to compete with new. That's the Model T effect that Ford experienced in the mid-1920s, when so many readily-reparable used Model Ts became available that Ford could no longer sell new ones at a profit. In addition, with the same basic style and performance since its launch in 1908, by the 1920s more stylish and more powerful cars were available from brands such as Chevrolet at an affordable price.

As a result, car prices fall over time; one careful analysis using US data suggests that happens at 9% per annum, or 40% over 4 years. While that may be on the high side, it suggests that discounting is inevitable. Now price drops aren't necessarily blasted in bright red 30% off ads. At launch, it's typical that only fully-loaded versions are available, not the base model. But many of the high-trim-level options don't actually cost much from a manufacturing perspective, so changing the production mix towards more base models is effectively selling the same car at an often sizable discount.

Of course, from an empirical perspective, at any given time there's a mix of old and new models on the market. That there are discounts from the original list price on older models is normal, not a sign of price wars.

Analytics: the factory perspective

Designing, engineering, manufacturing and delivering cars entail high fixed costs. In the best case, getting to Job One takes 18 months, and double that if it entails a new platform and not just new sheet metal and interior styling. A series of 5 stamping dies, one set each for right and left doors, can run $10 million. Multiply that for other stampings, for the injection molds for exterior and interior trim pieces, and for new brackets, and you quickly have spent $200 million, all before you earn a penny of revenue. You hand-build a bunch of "mules" out of pre-production parts to do road tests to check for noise and vibration and fine-tune handling. More expense, and if you find problems, potential lost delays, and time is money. Then there's production. The assembly line isn't particularly expensive, but the robots to weld the body-in-white are. The paint shops is worse, the highest-cost part of a modern car factory, with a phosphate wash, rinse, and e-coat bath, a paint booth or two (when the base coat needs drying time), and hundreds of feet of drying ovens. Furthermore, the airflow is critical, it has to be conditioned for humidity, and be able to carry away overspray but not so strong that it can't be precipitated out – painting the parking lots of neighboring businesses doesn't go over well. All that runs $350 million, and you run up a large utility bill to operate them, and an even larger bill to bring them up to temperature if they are shut down.

Then there's labor. Workers may be paid by the hour, but you can't run an assembly line with staff at only half the stations. So when sales slow by 10% you can't reduce your headcount by 10%. Of course a plant can run on short hours, but workers won't stick around if you only offer them 30 hours a week. In practice, then, labor is a fixed cost.

Now there are variable costs for the thousands of components purchased from suppliers, which likely account for 80% or more of production costs. Even there, car companies commit to a minimum production volume. That may be in the form of a take-or-pay contract. In addition, the costs for supplier tooling are added into the price for the first year or so, sometimes with a bump to cover engineering specific to a given model. Since car firms need components for other models, and for future models, they can't play hardball. Of course suppliers are also ongoing businesses, so may not try to enforce take-or-pay provisions. So for a car company hitting target volumes is pretty important, it keeps their suppliers quiescent, and once it reaches a certain level, supplier development costs are amortized and unit costs fall.

The fixed cost dilemma

Recouping high sunk costs requires attaining target volumes. Covering the fixed costs of production requires keeping the factory running a standard work-week. Suppliers expect to cover their costs, and you have to keep trucks available in good times and slow to get cars to their delivery point.

That of course is your problem as a manufacturer, and consumers don't always cooperate. You know that if you can hit sales targets you will eventually see your unit costs fall, and be able to profitably discount as a model ages. If sales are poor, however, you lose less money by discounting a model than by stopping production. In the latter case you have to write off all those up-front development costs, and if you have to close a plant, you won't be in a position to make that new model that proves to be a hit.

So there's always the latent potential of a price war.

Tacit cartels and stability

Think of the Big Three, back in Detroit's glory days of the late 1950s and 1960s. Ford, GM, Chrysler would make minor changes every year, a facelift every other year, and a full model change every fourth year, with staggered timing across their model lineups so that there was always one or two brand-new offerings. GM was the 800-pound guerrilla with 50% market share and the lower costs that came from high production volumes ("economies of scale") and a broad product portfolio ("economies of scope").1 The industry engaged in a choreographed dance. In most years GM would announce prices first, and then Chrysler and Ford would follow with similar but slightly lower prices. (No one cared what American Motors did...) Of course GM set prices high enough to anticipate a nice profit (in its heyday, at a 20% return on investment), and its smaller rivals would do their best to eek out a decent return. Only once did that comfy arrangement break down, in 1955, with reciprocal price cuts of smaller cars.2

What might lead to a loss of discipline? Of course demand uncertainty is part of the story, if sales are expected to be slow, car companies won't be aggressive in their pricing, and firms with weaker product offerings will find it more tempting to undercut rivals' prices. That's particularly the case for ICE offerings, as with BMW, VW and GM – ICE discounts averaged 元56,700 while PHEVs discounts averaged 元22,200.3 Supply shifts are another source of uncertainty. In particular, the price falls in of lithium batteries make it harder to set a target price for EVs and, to a lesser extent, PHEVs. We do indeed find that at an average of 元30,000, EV discounts with their larger battery packs were 35% higher than those of PHEVs.4

Is there a price war?

On the face of it, the gross patterns of discounting make sense. Prices naturally fall over the model cycle.5 The collapse in ICE demand suggests bigger discounts there; that’s what we observe. The supply side expanded more for EVs than PHEVs, and we indeed find more discounting for EVs.

At the same time, there’s anecdotal evidence suggesting a cascade, with discounts (5 year, 0% financing) spreading from an initial firm to others, starting with Tesla and BYD and spreading to others.6 The Model 3 also receives a 元8,000 “insurance subsidy,” while others advertise a cash bonus for trade-ins. That sounds like a price war.

Still, BYD slashed prices across the board in February 2024, rather than just prices of specific models, suggesting that the driving factor was lower costs, not a sudden breakdown in discipline.7 Tesla, meanwhile, needed to clear inventory prior to the early-2025 launch of the refreshed Model Y. There were very large discounts to clear inventory as new emissions rules took effect in 2023, but those then disappeared (as did dealers’ stocks of non-compliant vehicles). Meanwhile, provincial government and then national-level incentives (the “new-for-old” subsidies are for an array of consumer durables, refrigerators and so on, and not just cars). That muddies the picture.

The Bottom Line

Competition remains viscious, with many new entrants with new assembly plants unable to achieve volume sales. Exits continue, with Hozon (and its Neta brand) apparently closing its doors. (Sales peaked at 47,000 in 2022Q3 but total only 536 in Jan-Feb 2025.) The drop in joint venture production has likely rendered Dongfeng, FAW and perhaps also SAIC unprofitable. Even if there’s no price war, there are too many players and a market that, despite a renewal of “new-for-old” incentives shows no sign of growth this year. With low capacity utilization, the overall industry may well be losing money even if select firms remain profitable (BYD, Geely, Tesla).

In closing, here’s an ad from https://car.yiche.com/haiou/ for the BYD Seagull, showing a 元3,000 discount, or about $400 off. That’s only 4% off the 元69,800 sticker price, so within the range a buyer might expect to be able to negotiate. Of course, if that’s combined with a 元15,000 new-for-old discount the price drops to 元51,800 or 26% off, and the price will be even lower for those able to avail themselves of an additional provincial or municipal subsidy.

It’s a buyers’ market!

Economies of scale are much higher in producing engines and transmission than in assembling cars. Having a broad product lineup with copious sales allows a car company to offer a range of engines at a lower cost than otherwise.

GM dominated the market for larger, more expensive cars. Those prices didn't change much.

Using the data in note 4, and 40 kg of lithium carbonate per kWh of LFP batteries, costs for the 29 kWh of batteries that might be found in a PHEV fell 元21,000. A pure EV has double or triple that amount of battery capacity, with a commensurately larger drop in costs.

Luis Cabral's Introduction to Industrial Organization (MIT Press, 2nd edition 2017) offers a nice explication of theory and empirical examples of the periodic breakdown in tacit cartel stability.

Note that the averages I report are not sales-weighted. I did check whether that matters – while it may seem counter-intuitive, weighting leads to a higher average discount. Why? – large discounts work, boosting sales!

Finally, on March 20 SG-Auto reported that from 2023 to 2024 battery-grade lithium carbonate prices fell 65% to 元91,000 per metric ton, and by March 18 had declined an additional 17% to 元75,900. See https://www.sg-auto.com.cn/List/ArticleView/9856, 新能源车平均降3万元,超八成经销商价格倒挂. The overall article argued that for NEVs, cost declines were a big factor, paralleling my argument. It did note one implication: discounts mean that 80% of joint venture car dealers are “upside-down” with the prices they paid for the inventory on their lots higher than what they will now earn from selling those cars.

In my China sales dataset I can track the launch data of models that have new names, but I have not tracked when a new model is released with the same name. Impressionistically, that's more relevant for the brands of VW and others, produced in joint ventures, because they have a full product lineup so keep existing, recognized model nomenclature. In contrast, most of BYD's models are recent launches with new names. Of their 23 models with over 1,000 units sold in February 2025, only 3 were launched prior to 2020, while 8 models are less than a year old and 5 are less than 2 years old. At the other end, 6 models sold in January 2020 are no longer produced. BYD is a young firm: in 2020Q1 BYD sold only 25,554 cars; in 2024Q4 it sold 1,251,674 or almost 50 times more, with February 2025 Seagull sales alone topping 2020Q1.

“In November, the "price war" in the auto market continued to heat up, with the highest discount reaching 110,000 yuan”, Loey on Gasgoo, 2024-11-26 07:39:35 at https://auto.gasgoo.com/news/202411/26I70411616C501.shtml. [In Chinese, but Google Translate does a reasonable job.}

See “China's EV war: BYD, peers take discounting to new lows at expense of margins,” Daniel Ren, South China Morning Post, 10 October 2024.