Introduction

Bringing automotive jobs to the US is already part of the IRA, with its focus (among other sectors) on EVs and the battery supply chain. That’s a long-term policy, and faces the challenge of consumer resistance to EVs and the challenge of adding battery capacity in the face of improvements in chemistry that are faster in clockspeed than plant construction. Solid-state formats, sodium-ion batteries – there are lots of developing technologies. No more here on that issue, which is even more pressing in Europe with its more stringent emissions policies.1

Jobs

There is however an ongoing challenge to all of manufacturing, finding workers in the face of an aging population and an education system dominated by a college prep curriculum and the pull of the service sector.2 In automotive that is offset by the rise of productivity, which has helped the US maintain output with fewer workers. I build the rest of this short article around graphs in my chapter in a book out this fall, The North American Auto Industry since NAFTA, University of Toronto Press, edited by Greig Mordue and Dimitry Anastakis.

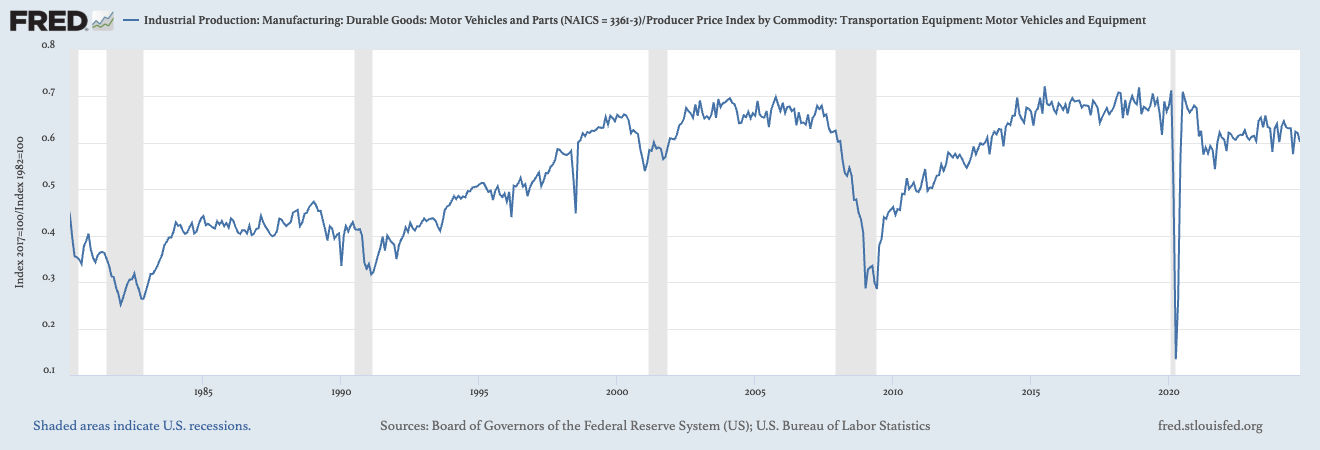

There are multiple series with different conceptual bases. The first and foremost point is that for the industry as a whole labor productivity has risen 10-fold over the past 55 years.

At a narrower level we can see that parts manufacturing has seen continued productivity improvements, whereas recently assembly productivity has declined. Of course – if you follow the industry – that decline corresponds to the disappearance of much sedan production, as the Detroit 3 shifted their product mix almost entirely to light trucks, and truck plants are more complicated because of higher variety (short and long bed pickups, extended and crew cabs, and full-sized SUV variants).

This should be surprising, due to the increased complexity of a modern vehicle, which can have 300 lbs of wires, turbos and start/stop systems, and numerous sensors for parking (ultrasound “bubbles” in the bumpers), lane departure warnings (cameras in the outside mirrors), automatic high beams (a forward camera) and adaptive cruise control (radar and cameras). As Mordue and Anastakis stress in their introduction, high parts productivity in the US is enabled by the shift of labor-intensive production out of the US and Canada to Mexico (and elsewhere), so they don’t observe productivity increasing for the USMCA as a whole.

Note that real automotive output – that is, the value of output corrected for inflation – has been relatively flat. Other metrics, such as output as measured in GDP, show similar changes. (The graph starts in 1980, NAFTA took effect about the middle of the graph, and there are big dips with the Great Recession in 2007-10 and COVID in 2020.)

OK, so what of the bottom line, jobs? Let’s start with ones in automotive. Monthly Bureau of Labor Statistics data show the peak at 1.34 million in 1994, and 1.08 million in August 2024. That’s a drop of 260,000 or 19%. Employment in assembly plants is little changed over the past 35 years; the drop is entirely in parts production.3

So on the face of it, tariffs can lead to jobs in parts production shifting back from Mexico and Asia. However, those jobs are on average labor-intensive, hence any reshoring would result in higher costs.

But there’s a macro challenge, because the policies proposed by the incoming Trump administration would affect all of manufacturing. So what’s been happening to the sector as a whole?

Surprise, surprise: we’re a service economy. Manufacturing in the US expanded tremendously during WWII, but started declining as a share of jobs immediately thereafter.4 Note that while there appear to be discontinuities in total employment following the creation of NAFTA in 1994 and China’s entry into the WTO in 2001, that’s not true of the share of manufacturing in employment. In contrast, healthcare alone now employs almost 50% more workers than all of manufacturing.

So can we reshore? First, building new factories will take years, so the impact will be after the next administration. Second, automotive plants require high-quality workers; my son has worked at 4 different local factories, none of which produce at the requisite quality level. And all are finding it hard to recruit, even with a slow but steady increase in wages. There simply aren’t a lot of factory workers to be had – and my son plans to become an electrician, shorter hours, better pay and no commute. (Similarly, one of his high school classmates shifted from a factory to be a cood at Waffle House, better pay and working conditions, and hours that don’t eat into his music gigs.) Third, new plants don’t necessarily locate in the same places as the old, though the work by Thomas Klier and his colleagues at the Chicago Fed show that new plants remain concentrated in the “Auto Alley” that stretches along the I-75 corridor.5

Finally, reshoring will be inflationary, and the lack of attention to high prices appears as one of the key factors in Trump’s electoral victory. Labor-intensive manufacturing migrates to places with lower wages, particularly for goods that are easy to transport. In addition, tariffs themselves are inflationary, as they are paid by the importer and so ultimately get passed on to consumers.6

Conclusion

With 100% tariffs, inflation will arrive quickly, jobs slowly if at all.

Afterward

Note that most “automotive” jobs are downstream in dealerships, insurance, tires and service, leasing and other sectors. Those sectors employ over 3.8 million workers, so are far more important than manufacturing. Almost none of those are affected by trade – a repair technician has to be local.

I visited one of Europe’s leading automotive battery manufacturers in June 2024 as part of the annual GERPISA conference. Battery plants are very capital intensive, as lithium is flammable and purity is critical, so the core processes in a large, very dry clean room. Workers wear breathing masks so their exhalations don’t drive up the humidity. Yield is critical to controlling costs, so the work is also very intense. Such jobs are not for everyone!

A particularly sobering account is in the November issue of the Atlantic. Though the article’s primary theme is the rise of a finance-driven meritocracy, it stresses that the impact is felt throughout the food education chain. David Brooks, How the Ivy League Broke America, The Atlantic, Nov 14, 2024.

The data do not capture all of the “upstream” value chain, as a steel mill or paint manufacturer that ships most of their product to the auto industry are likely classified as belonging to other industries. The industry, for example, uses a lot of computer chips, but pales in scale alongside that of the computer industry in its many guises.

Consistent BLS data collection started only in 1948, so I can’t provide earlier data. Economic historians of course have their estimates, as a search of EconPapers will find.

See Thomas Klier and James Rubenstein, “The Emerging Geography of Electric Vehicle Production in North America: Revolution or Evolution?” Economic Perspectives, 2024:4. He also has a chapter in Mordue and Anastakis. Most of the chapter authors, myself included, have known each other for a decade or longer.

Basic Econ 101 of course notes that they tend to lower the price received by the exporter, but that’s a function of supply elasticities, and I believe that in automotive they have little ability to absorb lower costs.